The National Security Agency designated the University of Arizona's Cyber Operations program as a Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Operations (CAE-CO). With this designation, UA joins an extremely exclusive group of only 24 cyber programs in the nation. The NSA's CAE-CO designation demonstrates that UA's Cyber Operations program meets the most demanding academic and technical requirements.

The Bachelor of Applied Science in Cyber Operations prepares graduates for cyber-related occupations in defense, law enforcement, and private industry.

Our curriculum includes both offensive and defensive cyber security content delivered within our state-of-the-art Virtual Learning Environment to ensure our students have extensive hands-on experiences to develop the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to succeed after they graduate.

Cyber

Engineering

Defense

& Forensics

Cyber Law

& Policy

Program News

DoD Cyber Scholarship Program (CySP)

The DoD CySP is a yearly scholarship program aimed at Juniors and Seniors pursuing a bachelor’s degree in cyber-related academic disciplines. The CySP is a 1-year scholarship, which grants selected Cyber Scholars tuition and mandatory fees (including health care), funding for books, a $25K annual stipend, and guaranteed employment with a DoD agency upon graduation.Cyber News

The Justice Department has formally proposed new regulations that would prevent or restrict the selling and transferring of Americans’ sensitive personal data to adversarial countries.

The proposed rule, first previewed in March, stems from an executive order issued by the Biden administration in February and imposes a series of restrictions on how American entities can sell “bulk” sensitive data across six categories: personal data like driver’s license and Social Security numbers, precise geolocation data, biometric identifiers, human genomic data such as DNA, health information and financial information.

It would also impose a blanket prohibition on selling such bulk data to six nations — China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba and Venezuela — designated as “countries of concern,” meaning their acquisition of Americans’ personal data represents a potential national security risk.

The revised version, released Monday, adds new exemptions for telecommunications services, clinical trial data needed to obtain regulatory approval to research or market pharmaceuticals or medical devices in a country of concern, and clinical trial data needed for Food and Drug Administration applications related to pharmaceuticals and medical devices.

The revised rules also require companies to report third-party involvement in a sale, explain how the rules align with other federal bodies, like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, and provides unclassified examples of non-compliant transactions or behaviors.

“Under the proposed rule, U.S. persons transacting in these kinds of data will need to establish a compliance program based on the individual risk profile of their activities,” a senior DOJ official said. “They will need to understand the kinds and volumes of data they transact, who they are doing business with and how that data is being used, and the safeguards they use to control access to that data.”

Americans frequently share vast amounts of personal information through social media, online shopping, medical visits or government benefits. Companies collect and sell this data to larger data brokers, who compile granular profiles of consumers that can be sold to the highest bidder.

The regulation would prevent U.S. individuals or companies from directly selling personal data to foreign entities that are at least 50% owned by or located in a country of concern, foreign employees of contractors, foreign individuals who reside in countries of concern, or individuals specifically listed by the DOJ as a covered person.

Data brokerage, as well as transferring bulk human genomic data or biospecimens to any listed countries, would be barred under the rule. Vendor, employment and non-passive investment agreements, meanwhile, would need to pass requirements being developed by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency around encryption, data minimization, physical and logical access controls and privacy.

A senior Department of Homeland Security official said the security requirements will be based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s cybersecurity and privacy frameworks, and attempts to strike a balance between national security and freemarket economic principles.

“We’re seeking to achieve these goals as much as possible without disrupting free flow of data across borders, including by providing flexibility for various types of restricted transactions while, at the same time, not undermining the policy goals of the security requirements,” the official said.

Each category of data covered under the rule is subject to different thresholds depending on the sensitivity of the data. For example, a company would be prohibited from selling geolocation data on more than 1,000 U.S. devices to a company headquartered in China, or hiring a laboratory in China to analyze the DNA samples of more than 100 U.S. persons.

Meanwhile, a company that holds financial or health data for more than 10,000 U.S. individuals must follow CISA’s security requirements if it grants a Russian investor an equity stake, hires a China-based company for data storage or processing, or employs workers who primarily reside in China.

The DOJ, along with the Departments of State, Commerce and Homeland Security, would have the authority to issue licenses to bypass the proposed rules, but the government anticipates doing so “only in rare circumstances.”

The United States has lagged Europe and other parts of the world when it comes to updating privacy laws for the digital age and reining in data brokers who buy, bundle and sell massive amounts of Americans’ personal data to advertisers, marketers and foreign nations.

On a call with reporters, senior DOJ officials said the department received 67 comments on the advanced proposed rule and heard feedback from over 100 companies, industry groups and other stakeholders.

Brandon Pugh, director of cybersecurity and emerging threats at the R Street Institute, a right-leaning think tank, told CyberScoop that the new proposed regulations represent a “partial solution” to the problem of foreign countries gathering Americans’ personal data, but noted that current laws and regulations around data privacy in the United States still offer numerous pathways to accomplish the same goal.

“There are definitely ways that adversaries … are going to access this data, and this is not going to address them all,” Pugh said. “They can steal it, they can rely on data in breaches — or cause the breaches themselves.”

This year, a bipartisan group in Congress worked to agree on a comprehensive privacy bill that would limit the data that businesses can collect on their customers, shining a light on the largely unregulated data broker industry.

However, after initial optimism about the bill’s prospects, momentum stalled as the coalition fell victim to infighting and disagreement. It is not expected to move further this year with presidential and congressional elections just weeks away.

The post Justice Department rule aims to curb the sale of Americans’ personal data overseas appeared first on CyberScoop.

The cybersecurity firm Sophos agreed to acquire Secureworks in an all-cash transaction valued at $859 million, the two companies announced Monday.

Sophos, a privately owned United Kingdom-based cybersecurity firm, said it intends to integrate security solutions for all small, mid-sized and enterprise customers focusing on automated prevention, detection, and response using artificial intelligence.

“Secureworks’ renowned expertise in cybersecurity perfectly aligns with our mission to protect businesses from cybercrime by delivering powerful and intuitive products and services,” Sophos CEO Joe Levy said in a statement. “This acquisition represents a significant step forward in our commitment to building a safer digital future for all.”

Secureworks is an Atlanta-based cybersecurity firm that was founded in 1999 and acquired by Dell in 2011. With the Sophos deal, shareholders for Secureworks and Dell will receive $8.50 per share in cash, according to the announcement. The transaction is expected to close in early 2025 and the two organizations will continue to operate as “independent companies and it is business as usual,” Secureworks CEO Wendy Thomas said in a statement.

Thomas said she expects Sophos’ end-to-end security products and experience as a managed security service provider will complement Secureworks’ extended detection-and-response expertise.

“Sophos’ portfolio of leading endpoint, cloud, and network security solutions — in combination with our XDR-powered managed detection and response — is exactly what organizations are looking for to strengthen their security posture and collectively turn the tide against the adversary,” Thomas said.

Sophos was founded in 1985 and purchased by the private equity firm Thoma Bravo in March 2020 for $3.9 billion. Thoma Bravo made a slew of cybersecurity purchases in the past few years, including acquiring Proofpoint for $12.3 billion in 2021 and Darktrace for $5.3 billion in April 2024.

The post Sophos to acquire Secureworks for $859 million in cash appeared first on CyberScoop.

The U.S. government has announced a reward of up to $10 million for information about the Russian media organization Rybar and its employees, amid allegations it’s involved in spreading propaganda aimed at influencing the upcoming U.S. presidential election.

According to the State Department’s Rewards for Justice Program, Rybar has been accused of using its extensive social media reach, with over 1.3 million followers on various channels, to promote pro-Russian and anti-Western sentiments. The organization has allegedly established several contentious online platforms, which have sought to create social and political divisions within the United States. These efforts are reportedly linked to broader Russian strategies to impact U.S. electoral processes.

Rybar is said to have received financial backing from a state-linked Russian defense entity that is currently under U.S. sanctions. The media outlet, which was founded by deceased Russian mogul Yevgeniy Prigozhin, ran online channels inciting discord on issues such as immigration and political alignment, particularly in connection with ongoing conflicts.

Rybar controls social media channels like #HOLDTHELINE and #STANDWTHTEXAS to push Russian political interests in the United States. Earlier this year, Rybar set up a channel called “TEXASvsUSA” on X (formerly Twitter), which spewed rhetoric tied to illegal immigration.

The State Department called out nine people, including Mikhail Zvinchuk, who runs the blog.

https://twitter.com/RFJ_USA/status/1846566996458000702

This initiative is part of a larger crackdown on foreign election interference, reflecting growing concerns over the integrity of democratic processes in the face of international threats.

The announcement comes as the State Department has been heavily focused on calling out Russian propaganda. The State Department sanctioned RT and related media companies in September, accusing the Russian state-funded news outlet of operating a crowdfunding website that funneled weapons and equipment to Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine.

The post State Department offers $10 million reward for info on Russian propaganda outlet appeared first on CyberScoop.

A 25-year-old Alabama man has been arrested and charged with hacking into the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Twitter/X account earlier this year and making fake regulatory posts that artificially inflated the price of Bitcoin by more than $1,000 per unit.

Eric Council Jr., a resident of Athens, Ala., was arrested Thursday morning and charged with aggravated identity theft and access device fraud in connection with the January 2024 incident.

According to the Department of Justice, the FBI and the SEC Inspector General, Council and other unnamed parties used SIM-swapping to steal the identity of a third-party individual with access to the SEC’s main account. The attackers only maintained control of the account for a short time, but before the SEC and Twitter/X could restore access back to the agency, they published a post imitating Chair Gary Gensler and announced that the listing of Bitcoin on registered national securities exchanges had been approved.

While the SEC did indeed eventually approve the listing, the premature posting caused considerable market disruption, sending the price up by $1,000 per bitcoin before falling by $2,000 per bitcoin when the announcement was revealed to be fake.

An internal investigation by the SEC earlier this year had already determined that the breach occurred through a SIM-swapping attack via a telecommunications carrier, and confirmed that the agency’s Twitter/X account did not have multifactor authentication in place. SIM-swapping attacks use social engineering and other methods to induce carriers to re-assign a cell phone number to another device controlled by the attacker.

“These SIM swapping schemes, where fraudsters trick service providers into giving them control of unsuspecting victims’ phones, can result in devastating financial losses to victims and leaks of sensitive personal and private information,” said U.S. Attorney Matthew Graves. “Here, the conspirators allegedly used their illegal access to a phone to manipulate financial markets. Through indictments like this, we will hold accountable those who commit these serious crimes.”

According to authorities, Council Jr., who went by the online handles “Ronin,” “Easymunny,” and “AGiantSchnauzer,” was provided a fake identification card template and other personal information for the individual controlling the number attached to the SEC’s account.

According to the indictment, Council was tipped off by other co-conspirators that an individual, identified only as “C.L” had a phone number with access to the SEC’s Twitter account. They then used an encrypted messaging service to send Council personal information, an identification card template and a photo of “C.L” to create a false identity. The co-conspirators also relayed that “C.L” had a cell phone account with telecommunications carrier AT&T.

Council, who had his own identification card printer, printed out the fake ID and used it at an AT&T store on Jan. 9, 2024, posing as an “FBI agent who broke his phone and needed a new SIM card.” After obtaining a replacement card, he visited another cell phone provider store and used it to re-assign C.L’s cell phone number to his device, giving him control over the individual’s phone, its data and access codes for the SEC’s Twitter/X account.

He then passed those codes along to his co-conspirators, who posted the fake tweet. He was paid an unspecified fee in bitcoin and later returned the phone.

Authorities claim Council Jr. later conducted a series of incriminating internet searches for “SECGOV hack,” “telegram sim swap,” “how can I know for sure if I am being investigated by the FBI,” and “What are the signs that you are under investigation by law enforcement or the FBI even if you have not been contacted by them.”

The short takeover of the account and the financial impact of the fake post caused outrage in Congress and among identity experts, who expressed disbelief that a high-profile social media account for an agency with market-moving regulatory powers was hijacked so easily and did not use multifactor authentication.

A Scoop News Group review of federal rules and regulations around agency social media use found that while many agencies strongly encouraged or internally required their accounts to have multifactor authentication and other protections in place, there are no standard or mandatory rules requiring them to do so.

The Office of Management and Budget, which has the authority to implement cybersecurity policy across the federal government, repeatedly declined to answer questions from CyberScoop in the wake of the hack about whether federal agencies were required to use multifactor authentication for social media accounts.

Grant Schneider, who served as federal chief information security officer in OMB before leaving government in 2020, told CyberScoop that much of the authority OMB and other agencies have over civilian federal cybersecurity policy derives from the Federal Information Security Management Act, a law originally passed in 2002 and updated in 2014.

Because that law is focused on “federal information and federal information systems,” when an agency is using a social media platform that is not housing or processing federal data, “I’m not convinced that OMB or [the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency], at least under FISMA, has the authority to direct how agencies secure those accounts,” Schneider said.

The post Alabama man arrested for role in SEC Twitter account hijacking appeared first on CyberScoop.

The Federal Police of Brazil on Wednesday arrested a person allegedly responsible for a series of audacious data breaches targeting large international companies and U.S. government entities.

The suspect, who is known in the cybercrime underground as USDoD or EquationCorp, is allegedly the person responsible for a breach of the online background check and fraud prevention service National Public Data, exposing personal information and Social Security numbers of millions of Americans. Brazilian authorities also say the suspect is responsible for compromising the FBI’s InfraGard — a portal used by American law enforcement to share critical threat information.

The Brazilian police did not name the suspect. In August, Brazilian tech publication Tecmundo reported that CrowdStrike had given a report to Brazilian police naming a 33-year-old “Luan “B.G.” as the person responsible for breaching National Public Data. Shortly thereafter, a “Luan” told HackRead that CrowdStrike had doxxed him and claimed responsibility for the breach.

CyberScoop confirmed “Luan” is a 33-year-old Brazilian national via his Instagram account. Brazilian police could not be reached for comment.

Brazilian authorities arrested the attacker Wednesday in Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s sixth-largest city. Authorities said the suspect was arrested “under warrants issued for past illegal data sales, specifically on May 22, 2020, and February 22, 2022.”

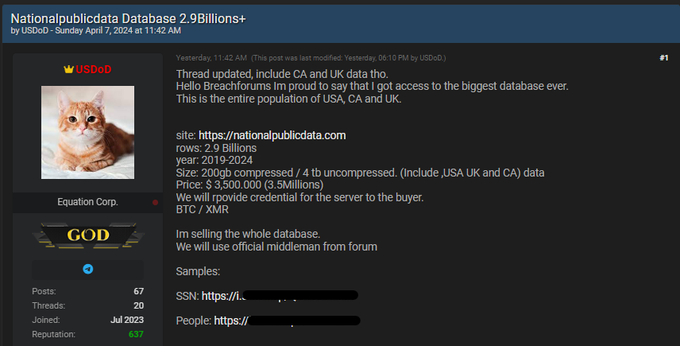

The data breach at National Public Data compromised 2.9 billion records, including full names, addresses, birth dates, phone numbers, and Social Security numbers. The stolen data spans at least three decades and was being sold on the cybercrime underground with server credentials for $3.5 million.

A screenshot of the listing on a cybercrime forum tied to the National Public Data breach.

A screenshot of the listing on a cybercrime forum tied to the National Public Data breach.

Brazilian police also say the suspect is responsible for data breaches on other entities, including Airbus and the Environmental Protection Agency.

This arrest marks another step in Brazil’s ongoing battle against cybercrime, following a successful operation earlier this year that dismantled a criminal group behind the banking malware Grandoreiro, which has defrauded victims of millions dating back to 2019.

The post Brazil’s Federal Police arrest alleged National Public Data hacker appeared first on CyberScoop.